What is an Evangelical?

In our era, “evangelical” has become a highly contested word, often associated with political movements in our nation and world. For years, I have reminded our congregation that “We are not a red church. We are not a blue church. We are a Jesus church” because we long to “keep the main thing, the main thing”. As a church family, we desire to be spiritually formed by the simple rhythms of grace – worship, prayer, scripture, community – all focused on Jesus.

Over the last 15 years, many evangelicals have given up on the term “evangelical”, viewing the word as severely compromised by the toxic political divisions in our country. Indeed, many people outside the church view the word as simply another moniker for a certain voting bloc or aligned with a specific demographic politically. They rarely realize the word has a long religious history.

Despite the recent attempt to colonize the word from the religious realm to the political sphere for its own ends, the word “evangelical” has a longer history than America’s recent political divisions. The word evangelical goes back 2,000 years to the New Testament Greek word euaggelion which is translated “gospel” or “good news”, appearing most prominently in the key thesis verses of Paul’s book of Romans:

For I am not ashamed of the gospel (euaggelion) for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes, to the Jew first and also to the Greek. For in it the righteousness of God is revealed from faith for faith, as it is written, “The righteous shall live by faith.” – Romans 1:16-17

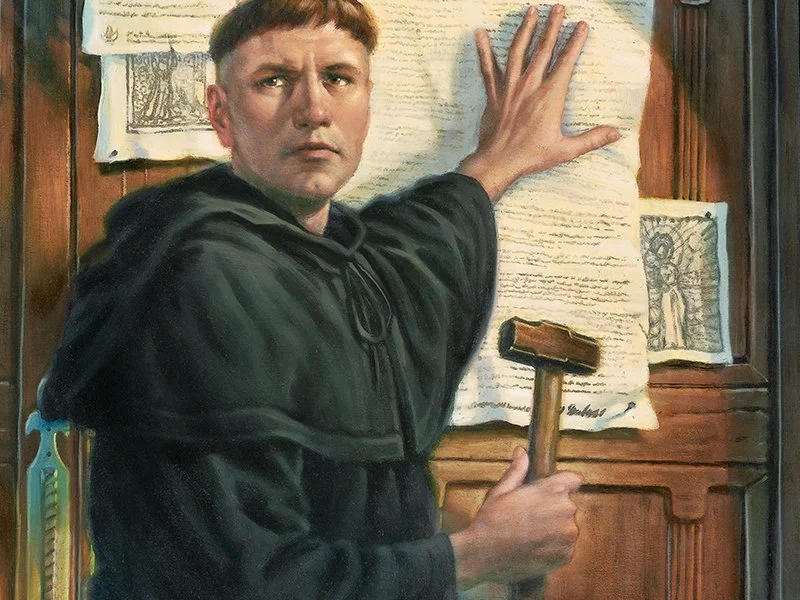

During the Reformation era, it was Martin Luther who sought to recover the gospel (euaggelion) and the righteousness of Christ that is ours through faith. The Protestant Reformation represented a vibrant spiritual recovery of the gospel of Jesus and what it meant to be an “evangelical Christian” – a believer who personally trusts in the gospel of Christ alone for salvation.

The 95 Theses of the Protestant Reformer Martin Luther called Christians back to the simple biblical gospel.

During the 20th century, an evangelical in America eventually came to be distinguished from fundamentalist Christians during the 1940s and 1950s. Whereas fundamentalists became increasingly separatist, anti-intellectual, and often legalistic vis-à-vis the modern cultural era, evangelicals sought an intelligent cultural engagement while keeping its grounding in the gospel of Jesus, in the inerrancy of scriptures, and in the substitutionary atonement. In the 1980s and 1990s, evangelical Christians left behind some of the “narrowness” and “legalism” of its fundamentalist forebearers through making major strides in scholarship by the writing of biblical commentaries, by setting up major seminaries for an emerging generation of leaders (i.e. Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School), and by becoming missiological thought leaders through major conferences like the Lausanne Congress of World Evangelization in 1974 organized by evangelical leaders like Billy Graham and the British theologian and churchman John Stott.

American evangelist Billy Graham and British theologian John Stott were central leaders of the Lausanne Congress of World Evangelization, held in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1974.

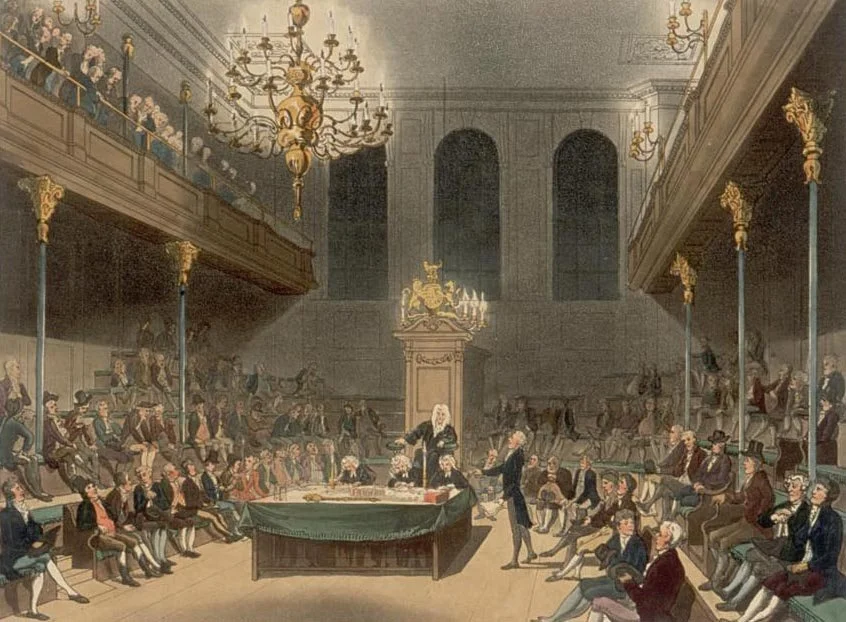

Therefore, when I utilize the word “evangelical”, I have three horizons in mind, none of which have to do with American political ideology. The first horizon is biblical – I use the word “evangelical” to describe a person whose affections have been captured by “the gospel” of Jesus. Simply put, an evangelical strongly believes in the simple biblical gospel to radically transform lives. The second horizon is historical – an evangelical is a person who is buttressed by the robust theological tradition of the Protestant Reformation and its five solas: salvation is by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone to the glory of God alone as revealed by the scriptures alone. Though many 21st century evangelicals are increasingly abandoning this rich theological heritage in favor of a non-theological and rather vanilla and shallow emotionalism based on the categories of self-help and pop-psychology, my own understanding of evangelicalism is anchored by names like Luther and John Calvin, with a historical thread continuing through the English Puritans John Owen and Richard Baxter, and sprinkled with intrepid names like the American theologian Jonathan Edwards and British preachers Charles Haddon Spurgeon (aka “The Prince of Preachers” -19th century) and Martin Lloyd Jones of Westminster Chapel (20th century) culminating in the post-WW2 evangelistic crusades of Billy Graham. Historically, modern evangelicalism boasts a robust preaching tradition which combines intellectual rigor with an evangelistic heart. The third horizon is cultural – evangelicals have often been unafraid to tackle the societal challenges for faith arising in the modern and postmodern eras, whether the rise of science, the challenge of poverty, the problem of abortion, and the question of marriage. This unafraid cultural stance, epitomized by William Wilberforce who successfully campaigned the British Parliament to put an end to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, drives the modern evangelical impulse. A culturally winsome evangelical longs for the Christ-centered renewal of all things both at home (homelessness, prison ministry) and abroad through its global missionary efforts (unreached people groups, church planting, majority world theological institutions).

The British evangelical Christian, William Wilberforce, courageously and tirelessly campaigned against the Transatlantic Slave Trade, with the British Parliament passing the Slave Trade Act on March 25, 1807.

One of the most famous definitions of the modern evangelical movement is described in the so-called “Bebbington quadrilateral”, proposed by historian David Bebbeington in his 1989 book Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s, where he argues for four distinguishing characteristics of evangelicalism:

(1) Biblicism – a high view of the Bible as the Word of God and the ultimate authority in faith and life.

(2) Crucicentrism - a central focus on the atoning substitutionary work of Jesus Christ on the cross.

(3) Conversionism – the belief that men, women, and children all need to be spiritually transformed through being “born again” through a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

(4) Activism – believers inherently express their gospel convictions through personal efforts in evangelism, missions, and societal reform.

What does this all mean? Evangelicalism, when it fully embraces its healthiest forms and expressions, can unabashedly drive forward the gospel of Jesus Christ in this broken world by being thoroughly committed to a high view of the scriptures through a laser-like focus on the cross of Christ in being unapologetic in calling all people to a personal relationship with Jesus while simultaneously working tirelessly and courageously for cultural renewal and the missionary enterprise in furthering the Kingdom of God.

On our best day as a church, we long to be biblically, historically, and culturally “evangelical” in the best sense of the word: committed to the gospel, committed to a high view of the transformative Word of God, committed to the simple message of the cross of Jesus that saves sinners, and committed to a winsome cultural engagement and to strategic missionary activity in all the world.